Last week, a couple of colleagues and I were having the “how can we learn from near misses if nobody reports” debate. One woman, a patient safety specialist frustrated with the lack of reporting, named a variety of situations she considered a “near miss.” The second, a nurse, decried the need to report things that don’t happen when the nurse is already stretched beyond her limit! “She should be praised for the good catch, not made to report!” I, as a risk management professional, saw the entire situation differently. Much of what was stated as a near miss is an “event” in my book that needs to be reported to be able to see vulnerabilities in order to prevent a patient from being hurt.

What really is a near miss? Is it a “whew” moment? If near misses are important as a signal to a latent hole in the system, why does the frequently quoted AHRQ Patient Safety Primer definition imply that the situation has reached the patient? If we catch a latent error well before it reaches the patient, aren’t these still near misses? Being lucky doesn’t take away the ultimate potential danger to patient safety.

A number of years ago, on a beautiful day in late March, I was standing peacefully on the side of a mountain…sun in my face. Out of nowhere, a youngster of about 11 came barreling down the slope and lost control. Before I could gasp, we were entangled on the ground. He bounced up and skied away. I was clearly in trouble, leading to an embarrassing ride down in the patrol sled and ski patrol assessment of my injuries. It was my left side, the impact side, that hurt…left knee especially. The local orthopedic doctor was a quick van ride away. His assessment: “You may be hurting on your left now, but by tonight, it will be your right knee ‘talking.’ You have lost your ACL.”

Fast forward through visits at my home orthopedic surgeon, MRIs, and scheduled surgery. The focus was clearly on the right knee…the one with a destroyed ACL. On the morning of surgery, however, when I went to admissions and was asked to sign the consent, I was stunned to read I was agreeing to LEFT knee surgery, not right. No! No! No! And in pre-op, you can be sure I made sure everyone knew it was the right knee, and NOT the left!

But how had this happened? And what if I wasn’t the type of patient who read everything, or what if I couldn’t read?

Likely the paperwork from the ski patrol and initial physician assessment had followed me to my surgeon. Perhaps the staff who filled in the blanks for the consent didn’t read the record carefully. But what if in the OR the staff marked the wrong knee…or someone checked the consent and said, “Oh she said right in the pre-op, but she consented for left”…or…any number of things we can’t even imagine.

Adverse events are pretty easy to spot. An adverse event is generally considered to be: “An event, preventable or non-preventable, that caused harm to a patient as a result of medical care. This includes never events; hospital-acquired conditions; events that required life-sustaining intervention; and events that caused prolonged hospital stays, permanent harm, or death.” That’s pretty specific: A patient harmed equals an adverse event.

Where it gets muddy is in that nebulous realm of near misses. Most healthcare professionals think of a “near miss” as “an unsafe situation that is indistinguishable from a preventable adverse event except for the outcome. A patient is exposed to a hazardous situation but does not experience harm either through luck or early detection.” When I read this, I think, “So if it didn’t reach the patient, it’s not a near miss. I don’t have to report this.” It was no harm, no foul. To make it more confusing, the AHRQ in the “Common Formats for Reporting” section (page 12358) defines near misses or close calls as “patient safety events that did not reach the patient.”

It is no wonder that it is difficult to get healthcare professionals to take the time to report near misses. Although it may be challenging to estimate what doesn’t happen, a recent pediatric surgery study specifically focused on near-miss reporting showed that only 1 in 137 observed near misses was reported. If we think about this one report as the tip of the iceberg, it’s pretty clear that near misses are not generally being part of our patient safety efforts.

So what’s at issue here?

Is the definition of near miss wonky? Yes, it is. There is no clean, clear, accountable definition. Definitions seem to be outcomes based and situationally based. And there are too many definitions that can guide the decision whether or not to report! One author in an op-ed said he found 20 different definitions of “near miss.” I didn’t dig as deeply, but it certainly doesn’t surprise me! Since the definitions include “reaches the patient” and “no harm” as parameters, most people would consider the information as “nice to know,” but not “need to know.” Is it any wonder people who are busy and stressed do not feel compelled to report “no harm” if it’s merely a “near miss?”

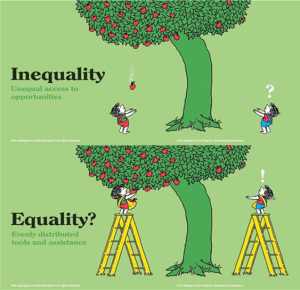

Harm will continue to happen if we do not find a way to identify the situations that cause it and stop them before they occur. Consider: What if we had a system of reporting that was 3-tiered:

- Adverse event that caused harm

- Adverse event that caused no harm

- Early catch

What if adverse events (both harm-causing and not) required reports that were simple and fast? And what if there were a simple, quick, and easy method for reporting near misses? If we can identify the key factors that lead to error, couldn’t we have a pithy report without a lot of detail for the “heads-up.”

I can imagine a world where both harming and non-harming adverse events are routinely reported and more people are being rewarded for early catching. Not necessarily with money, but perhaps with a “thank you; your caring may help save a future patient from harm.” It would make my day! What about yours?