Communication errors among providers continue to account for well over a third of all malpractice claims in the United States. This in spite of countless articles, classes, seminars, videos, and conferences in the past 20 years focused on improving communication among providers. In fact, The Joint Commission has made improved communication among healthcare providers a National Patient Safety Goal for 2018.

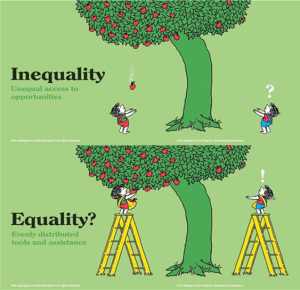

Which begs the question—what are we missing? It may be time to step away from the traditional methods and strategies we’ve used to talk about improving communication in healthcare and think outside the box. We know the statistics; the studies and research are out there. Perhaps it’s time to shift our focus and look at “why” we can’t seem to communicate well. Is it perhaps not what we are (or aren’t) saying, but what we aren’t hearing?

There’s no argument that healthcare has become more complex in the past 30 years. Primary care physicians must now interact with increasing numbers of specialists and other providers in caring for their patients. A 2012 report by the Institute of Medicine cited statistics showing that physicians in private practice caring for Medicare patients were required to interact with as many as 229 other physicians at 117 different practices each year. In addition, the average surgery patient was seen by 27 different healthcare providers while in the hospital. And EHRs, with their inherent lack of interoperability, also contribute to the complexity of the system. But we all know that—and still, patients are harmed because of a failure to communicate. Again, perhaps it’s a failure to listen.

And if that’s the case, how can we help providers become better listeners, and not just with their patients but with each other as well? What issues prevent providers from being better listeners? It’s too easy to blame the healthcare system, and ultimately, playing the blame game gets us nowhere. The healthcare system is made up of millions of stakeholders committed to making a complex system function better, with better patient outcomes and improved accountability, accessibility, and quality of life. We should be able to come up with the solution that’s evaded us all these years.

Given the system we have, where do we focus our efforts? Is it at the physician-resident level, teaching residents to listen more actively and providing incentives for residents to be willing to ask questions and yes—even be wrong at times so that they become better physicians and better listeners? Is it at the provider-provider level, working on breaking down the barriers among different specialists and encouraging collaboration instead of competition? Or is it more basic than that, looking at nurse-physician communication and seeking ways to encourage physicians to really hear what nurses are telling them at 3:00 am, when he or she has called with an alarming assessment of a deteriorating patient?

It’s likely that the answers won’t be simple, but perhaps if we approach this problem from a different perspective, we’ll have a better chance at improving this communication conundrum that has plagued us for so long.

What are your thoughts on improving communication by focusing on better listening? In your experience, what are the barriers to being better listeners, and what can be done to improve the way we listen? We’d love to hear from you and learn about novel approaches to address this important and ongoing issue.

Reference

Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013.

1 Comment to “Can You Hear Me Now?”

Residency 30 years ago taught us that women are better listeners and listen the required 2 minutes before speaking. I made sure I did and this served me well in ER 27 years.